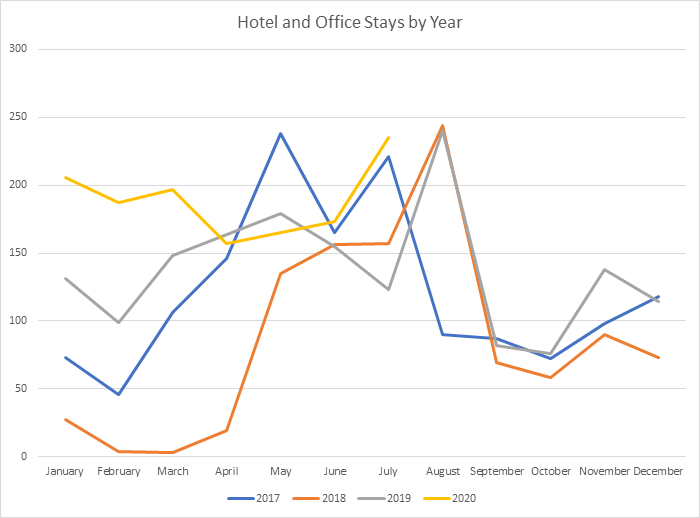

The past several years we have seen a disturbing and growing pattern of children in the foster care system having to stay overnight in a hotel with their caseworker, in a Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF) office or a one-night “emergency” placement in a foster home. Each of these situations is a problem. Children who have experienced the level of trauma these young people have experienced need a safe and stable place to live, with a safe and stable caregiver who can provide the level of care they need. They also need a level of therapy that is not typically available in hotels.

Additionally, the stays are expensive and disruptive to the normal functioning of DCYF offices and result in increased turnover of caseworkers – all negative factors. In 2017, the agency estimated the cost of a hotel or office stay at about $2,100 per night, which includes the cost of the hotel room ($150) and staff and security overtime ($1,950).

An occasional hotel stay is not a particular issue, as it is sometimes more disruptive to the child to organize a foster home placement in the middle of the night, but repeated one-night placements are dysfunctional. The number we have today is a systemic problem we are working to fix. All of our efforts include eliminating disparities in outcome by race in how the system works.

We will soon see an apparent spike in the numbers as we started collecting data in August on a related category of stays: overnight emergency placements. These placements happen when we have to negotiate with potential foster placements and they offer to take the child overnight (dropped off close to bedtime and picked up by the caseworker before breakfast) for rates that approach the costs the agency absorbs in hotel stays. The cost isn’t the main issue, it’s that we are creating a system that does not provide children with the stability they need.

Children with more than four hotel stay nights make up only 35% of the youth with any hotel stays, but they make up 83% of all hotel stays. The vast majority of stays are by a relative handful of children (around 250) with very complex behavioral health needs that most foster care families and even group homes are unable to safely serve.

It’s a complex problem and understanding our proposed solutions requires having a familiarity with the data about what makes these placements different than the thousands of other children in the foster care system. We see the increase due to several factors:

- A very small set of children who account for an enormous number of emergency placements.

- Our difficulty in finding placement options for children in King and Snohomish counties.

- Severe behavioral health issues for many of the children.

Large-Scale Changes to the Child Welfare System

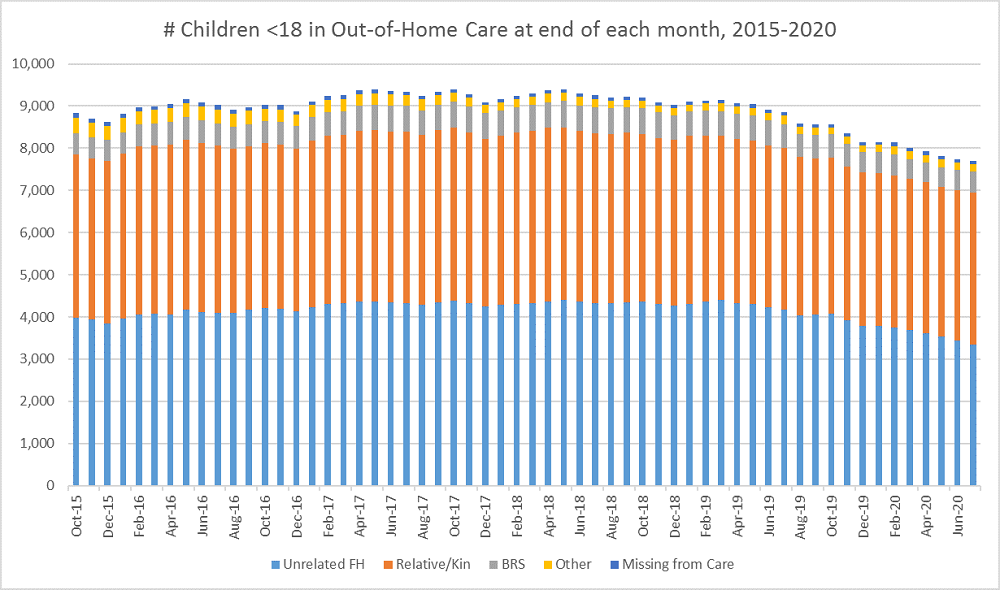

We are trying to solve this problem in the context of large-scale changes to the child welfare system to safely reduce the size of the system by half by 2025. In the past 12 months, we were able to reduce the number of children in foster care by 15%, which is well on our way to 50% over five years.

This large scale change has three components:

- Prevent child abuse and neglect with investments in home visiting, preschool and other primary prevention.

- Reduce entries to the system by the careful improvement of our practice, particularly around the assessment of safety, and by providing high-quality services to families as part of diverting them from foster care.

- Shorten the length of stay, particularly in King County. On average, children are in foster care for more than 600 days in Washington, which is the fourth worst in the nation. In King County, it’s nearly 800 days – almost a year worse than the rest of the state. We are accomplishing this with a collection of efforts, including speeding up adoptions and smoothing out the court process. We even asked for more lawyers in the Attorney General’s office last year.

You can read about our plans in summary and in detail in the following documents:

- Draft Strategic Plan.

- Performance Improvement Plan – a two-year federal plan to respond to specific concerns in the data about Washington’s performance.

Policy and Budget Changes

Our strategy to resolve this complex issue has several elements:

- Increase placements with family members instead of strangers and ensure adequate resources are provided to support the child.

- Improve the quality and availability of group home placements for youth with behavioral health needs.

- Increase management oversight of the practice with increased approval levels.

- Reduce emergency overnight placements in foster homes by limiting the available rate.

- Improve transitions between other kinds of facilities and the dependency system.

Kinship Placements

If we have to remove a child from their birth family, we focus on placing them with other family members, known as “kinship” placements. Children are almost always better off when they are placed with family or people they know, and it results in faster time to a permanent home and better mental health for the child. About 45% of the children in out-of-home care in Washington are with kinship placements, which is above average in the country.

We’ve made some changes to increase the focus on kinship placements and to ensure they have adequate resources to care for the child:

- There are many scenarios when everyone involved with a case agrees that a particular relative is the right placement for a child. But sometimes, that relative at some point, often long ago, was convicted of a “disqualifying crime” and the agency is prohibited from recommending placement there. We did a year-long process to change this list, removing 53 crimes from mandatory exclusion. The new Secretary’s List recognizes that people redeem themselves and that for many of the crimes listed there was no basis to believe it impacted a person’s ability to care for a child safely. It’s important to recognize the disparate enforcement of many crimes on people of color, skewing the ability for families to care for their own children.

- This year, we are proposing to the Legislature a dramatic change to how we license kinship caregivers, ensuring that they are considered for placement and get the resources needed to care for the child. Child-specific licenses will allow kinship caregivers a pathway in getting licensed that is more efficient and streamlined.

Group Homes

Our last option for a foster care placement for a child is a group home. We reserve these placements for children and youth who are difficult to serve in a traditional foster home. Washington uses group homes less than most other states, with a small fraction of our population served in them. For many years, we had seen a decline in the number of beds available in the system due to budget and rate cuts made in the last large recession. This pushed the agency to place an increasing number of children in out-of-state group homes.

There are some fixes to this system we are pursuing:

- Reduce the 80+ children who are in out-of-state placements. These are now down to 21, with most of the remaining placements being an appropriate option for the specific child, not a reaction to a shortage in Washington. We also increased the level of required court oversight of out-of-state placements to reduce this in the future.

- Last year, the Legislature approved a 45% rate increase for group homes. The rate increase resulted in stabilizing the existing system and several new options[1] that have gone through the licensing process and are now serving children.

- Also, we are now requiring group home placements to meet the federal Qualified Residential Treatment Program (QRTP) quality standard. All of our facilities have stepped up, become accredited and met the standard. This makes these programs more therapeutic.

Management Oversight

DCYF made significant changes in our management focus on this problem, increasing the level of scrutiny and approval needed to handle cases of multiple hotel stays. Remember, the problem isn’t a single overnight stay, it is young people having no stable place to live with a consistent caregiver, a stable school situation, etc.

- The DCYF Regional Administrator must approve children are being cared for in a hotel for four consecutive nights before a fifth consecutive hotel night occurs.

- The DCYF Assistant Secretary or the Director of Field Operations must approve cases where children are being cared for in a hotel for 10 consecutive nights before the 11th consecutive hotel night occurs.

- The DCYF Assistant Secretary or Director of Field Operations must re-approve cases that go over 24 nights, and again every two weeks after that.

Reduce Emergency Overnight Stays

In an attempt to reduce a practice that was growing in some regions, the agency changed the rate we are willing to pay for one-night emergency placements to $250. Any higher amount will need to be approved by the DCYF Assistant Secretary. This type of placement should be very infrequent and will have the same oversight as hotel stays.

Transitions From Other Facilities

One of the common problems we have that results in hotel stays is a youth arriving unannounced from another institution. In many cases, significant planning could have occurred and we are now engaged in this work. The Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) and DCYF now have top-level quarterly meetings to go over placement transfers, and mid-level staff are now coordinating these regularly. We see youth with hotel stays where their prior placement was a Behavioral Rehabilitation Services (BRS) facility, the Youth Study Treatment Center or other Children's Long-term Inpatient Program (CLIP) facility, county detention, hospitals (often for the treatment of behavioral health issues), crisis housing and Juvenile Rehabilitation (JR). JR transfers are internal and these are now being coordinated in advance.

Planning for the Future

In addition to making the whole system smaller, Washington needs more options for children and youth with severe mental and behavioral health challenges. We have fewer resources for children with complex mental health needs than almost any other state. Some of these are in DCYF’s area of responsibility and some are the responsibility of other agencies.

- More CLIP beds: The largest provider in this space is the Child Study and Treatment Center located on the Western State Hospital campus, but there are less intensive options that are more widely available. The supply of these beds is constrained by the legislative budget.

- Continued development of new categories of group home created by the Legislature last year – BRS+ and EPS+: It’s important to point out that the appropriate solution here is not Emergent Placement Services (EPS) beds, it’s long-term stable placements that teenagers who have experienced much trauma are willing to stay in.

- Create a new option: professional family placement that has the training and experience to work with children who have experienced extreme trauma and have predictably-difficult behaviors as a result. We have a joint grant with the Washington State Health Care Authority and should have some pilot beds in this category in October.

[1] Helping Hands Jace House- BRS/ five bed staffed residential, Golden Youth Services #5- DDA contracted site/ three beds, Bogden House WA- Medically Fragile contracted site- five beds, Foster First Orca Program- BRS/ 12 beds